ONE Anglican archbishop has already resigned after questions about his failure to investigate and act on reports of abuse within the church. Many other leading church figures, in both the Church of England and the Catholic Church, have been embroiled in allegations of abuses dating back decades and cover-ups that have continued. The General Synod is meeting this week, and among its motions is an attempt to formulate a safeguarding policy that will prevent any repeat of former abuses.

ONE Anglican archbishop has already resigned after questions about his failure to investigate and act on reports of abuse within the church. Many other leading church figures, in both the Church of England and the Catholic Church, have been embroiled in allegations of abuses dating back decades and cover-ups that have continued. The General Synod is meeting this week, and among its motions is an attempt to formulate a safeguarding policy that will prevent any repeat of former abuses.

So what better time to see John Patrick Shanley’s play Doubt – A Parable, and what more passionately felt production than Lindsay Posner’s at Bath Theatre Royal’s Ustinov Studio. This is a play that asks many more questions than it answers, and it was the writer’s intention that that “doubt” would leave the theatre in the minds of the audience, as strands and nuances of the words and performances came back into their memories.

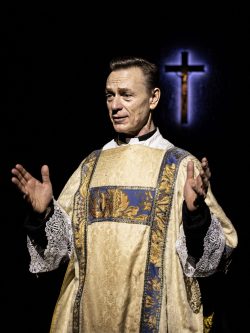

With Maxine Peake and Ben Daniels in the central roles, the stage is set for a monumental battle, that, to all intents and purposes, starts with Father Flynn’s sermon in the Church of St Nicholas in New York’s Bronx, one Sunday in 1964. The charismatic, warm and physical priest is beloved of his congregation and community, who include the pupils of the attached school over which he has pastoral care.

With Maxine Peake and Ben Daniels in the central roles, the stage is set for a monumental battle, that, to all intents and purposes, starts with Father Flynn’s sermon in the Church of St Nicholas in New York’s Bronx, one Sunday in 1964. The charismatic, warm and physical priest is beloved of his congregation and community, who include the pupils of the attached school over which he has pastoral care.

The school is run by nuns led by Sister Aloysius Beauvier, widowed in the Second World War and now running St Nicholas School with a rod of the most uncompromising iron. Both her staff of nuns and helpers and her pupils regard her with something akin to terror. Her strict disciplinarian regime is reinforced by her certainty, and it is that creed of certainty that Fr Flynn attacks in his sermon. Everyone, from time to time, has doubts. It’s is part of the human condition, he says. And off he goes to lead the boys in their sports.

Sister Aloysius, who regards everyone as suspect in a world where no-one can reach her exacting standards, wants him watched, so she inveigles the young and inexperienced teacher Sister James into looking out for any hint of vulnerability. Before long the junior nun comes to her superior to report an incident, and Sister Aloysius prepares her attack.

At the end of 90 tense minutes, we are asking ourselves if Fr Flynn is a serial predator whose progress Sister Aloysius is determined to halt or if she is taking out her own misery on a popular, caring and totally innocent man.

Maxine Peake’s Sister Superior is a masterclass in bitter, driven conviction. There are moments when, in the intimate confines of the Ustinov Studio, the shaking of her hands is painful to watch as she gears herself up for the next phase of her assault. The wellbeing, the happiness and the security of her young charges is forgotten in her crusade.

Maxine Peake’s Sister Superior is a masterclass in bitter, driven conviction. There are moments when, in the intimate confines of the Ustinov Studio, the shaking of her hands is painful to watch as she gears herself up for the next phase of her assault. The wellbeing, the happiness and the security of her young charges is forgotten in her crusade.

But what if she is correct in her observations of Fr Flynn’s behaviour. How many students will she have saved?

It is easy to see why people are drawn to Ben Daniels’ Fr Flynn. He is full of life and joy and hope – all things Sister Aloysius suspects as venal human faults. His capitulation is shattering, but is it because of guilt, because of fear, or because he knows that those above him in the hierarchy will not only sweep his crimes under the ecclesiastical carpet but promote him in the diocese?

Holly Godliman makes her very impressive professional debut as the confused and fearful Sister James, and Rachel John gives the lie to any preconception of a mother of the only black boy in the school, bringing powerful dignity and selfless love to the reality of this woman’s life.

Holly Godliman makes her very impressive professional debut as the confused and fearful Sister James, and Rachel John gives the lie to any preconception of a mother of the only black boy in the school, bringing powerful dignity and selfless love to the reality of this woman’s life.

This is another triumph for Theatre Royal Bath Productions, and continues at the Ustinov until Saturday 8th March.

Go back through the play in your mind and you will find yourself questioning what happened, and where and when it happened, and whether you heard it right. However we measure out the blame and the responsibility, it is never an easy decision, and every individual analysis has a slightly different focus. The current polarisation of society, internationally, will decide which side you are on. In 1964 people did it without the “aid” of social media. It’s a different world now, but the moral questions remain the same … no doubt about it.

Go back through the play in your mind and you will find yourself questioning what happened, and where and when it happened, and whether you heard it right. However we measure out the blame and the responsibility, it is never an easy decision, and every individual analysis has a slightly different focus. The current polarisation of society, internationally, will decide which side you are on. In 1964 people did it without the “aid” of social media. It’s a different world now, but the moral questions remain the same … no doubt about it.

GP-W

Photographs by Simon Annand